Dr. Francois Chevallier, PhD, Portfolio Manager, Machine Learning Strategies [email protected]

As the appetite for sustainable investing grows, investors are increasingly seeking investment options that go beyond the commonly available long-only equity ESG funds. Welton has written elsewhere, (“Solving the ESG Dilemma: How to Advance One’s Values While Also Improving Performance”), about how building in multi-asset class strategies into an ESG framework can improve performance.

But if we truly want to allocate our investment dollars in ways that solve some of our greatest environmental and social challenges and that gain wider adoption by the investment marketplace, we need to develop multi-asset ESG products that can help us build more sophisticated ESG portfolios. To do this we must first develop ESG scoring frameworks for these other asset types that can build adherents to these methods.

For consideration, I propose a framework that we have developed at Welton for measuring the ESG scores for derivatives instruments. Despite the fact that financial derivatives represent a very large proportion of the investment world, there have only been very limited attempts to study these instruments in an ESG context. It is our hope that by sharing this with the field, we can encourage others to weigh in and possibly improve upon this framework so that we can ultimately drive more widespread adoption of multi-strategy ESG products.

In the spirit of encouraging others to develop and share their own frameworks for scoring ESG derivatives, I think it is worth drawing out here in a bit more detail some of the challenges I encountered in developing this work.

But this is just one of many ways a more holistic portfolio construction can improve outcomes for ESG investors.

Back to the drawing board – and then back again

The primary goals of any such scoring methodology must be credibility, so that the measure can be trusted, and consistency, so that scores can be compared across instruments. In coming up with the proposed ESG methodology, I went down a number of different paths that proved unworkable.

In the context of my work at Welton, my initial interest was to be able to measure an ESG scores for Futures and Forwards instruments. Initial research quickly highlighted that it would not be possible to obtain ESG scores from a third party the same way one can for cash Equities. Part of the reason, at least, lies in that it is far easier to quantify the impact of a company than one of, say, agricultural futures. For example, consider the case of corn futures. While it seems pretty straightforward to consider the “E” (environmental) impact of corn production by measuring usage of factors like pesticide and water or carbon footprint, how would you go about measuring the “S” (social) or the “G” (governance)? And even if you could come up with a framework, it is unlikely that it would apply across the board to US Treasury Futures by virtue of the fact that the factors that drive sustainability are very different. For example, pesticide and water use are relevant for corn production, but not for Treasuries.

One way to develop a consistent methodology for derivatives is to look at the issuing entity of the underlying instrument (such as a commodity), as this data is reasonably easy to find and this approach is consistent with corporate ESG scoring. The most accessible common denominator across most derivative instrument are countries, for which data can be obtained from multiple sources. However, for this analysis to be credible, the source of the data needs to be credible and consequently, research for this project was limited to recognized international institutions.

We initially went down the path of using the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a unifying framework. But I realized that this became complicated very quickly because of the many overlaps between the S and the G characteristics. For example, government spending on healthcare and education (SDG 17) certainly sounds like a G factor, but what about the social outcomes of these policies, such as life expectancy at birth (SDG 3), which sounds like an S factor. But they are clearly very related.

In short, I realized that not only are there 17 different SDGs and that mapping these accurately would be complex, but that making determinations about the “E” “S” and “G” characteristics opened up the door to discretionary judgements – exactly what we wanted to avoid.

Ultimately our research led us to a Sovereign ESG data portal that has recently been developed by the World Bank. The World Bank ESG data framework classifies a set of 68 indicators relevant to the 17 SDGs into the three E, S and G pillars. We found the data coverage was to be impressive both in terms of geography and historical depth and the data can be easily accessed via a dedicated API.

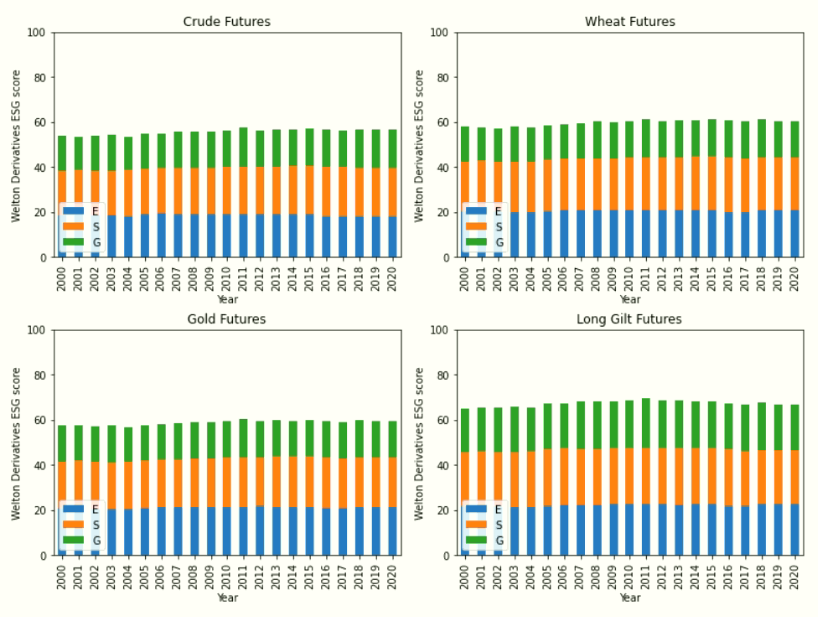

Having selected a data source, all we then had to do was develop a weighting score for the production of whatever was underlying each derivative, which required collecting more data from international institutions. Once the data had been collected and normalized, the sustainability scores were trivial to compute. Figure 1 below illustrates the evolution of the ESG scores and their sub-components for selected Futures markets.

The framework we developed is dynamic and is applicable to any financial instrument And the resulting ESG scores can easily be used to measure the sustainability of cross-asset portfolios.

Where we need to go from here?

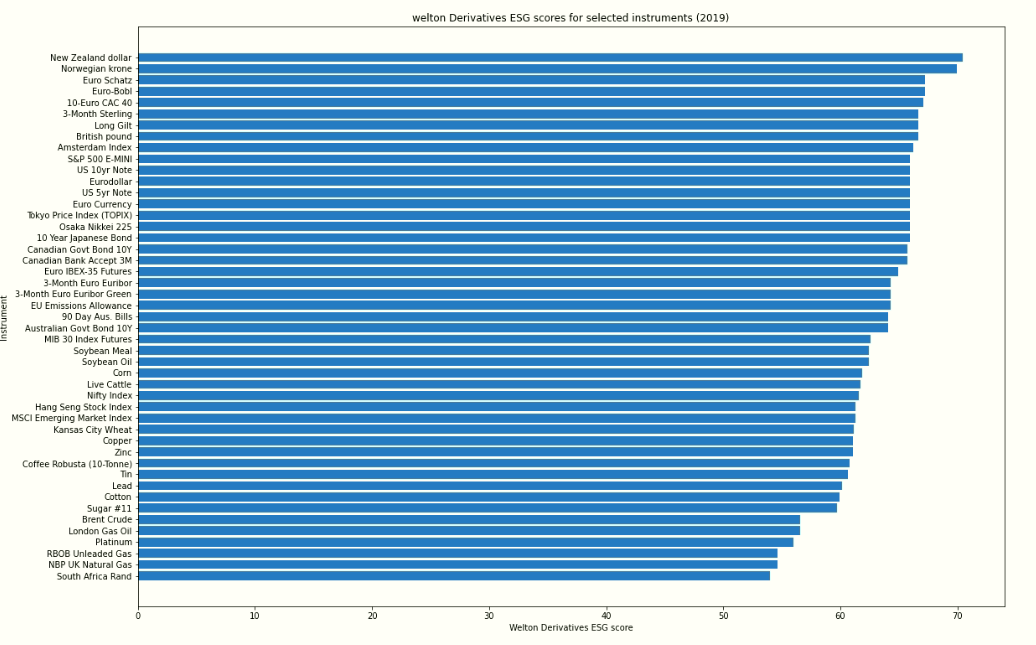

However, this framework also has two important limitations: the first one that the input data is only published annually, which limits its responsiveness to underlying shifts taking place over this period, so this is not ideal. This limitation could be remediated, however, by incorporating higher frequency indicators based on news or social media (which are currently an area of active research for Welton). The other important limitation of the current framework is that it tends to penalize commodities as highlighted in Figure 2 below.

Further inspection reveals that this bias is caused by the sustainability indicators themselves which tend to favor developed economies (especially the ones belonging to the S and G pillars) which tend to be issuer/producer of Financial instruments rather than commodities. Conversely, developed economies, which tend to have lower sovereign ESG scores, are more likely to be produce commodities. This bias needs to be acknowledged when making direct comparison between instruments’ ESG scores.

We invite others to share with us your thoughts on our framework as well as any efforts you have made down this path. We are convinced that ESG is perhaps the most significant and important shifts in investing in more than a generation. To fully realize its potential, we must come together as an industry to develop the methodologies that can help it gain broader acceptance among institutional investors.